A TWO-PART LOOK AT THE DATA BEHIND ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNERS IN ARIZONA

Eleven years ago, nearly 20 percent of Arizona’s public students were not proficient in English – meaning their primary language was non-English. Today, between 4-7 percent of our students are classified as not proficient in English. These statistics seem puzzling, given Arizona is a border state, has an increasing K-12 population and is commonly thought of as growing in diversity. Either the data is askew or our rapidly rising K-12 population has a lot more English speakers than it once did.

Regardless of the percentage of Arizona’s students that are classified as non-English speaking, student achievement and outcome data suggests Arizona is doing a poor job for this important population. The Association has recently analyzed AzMERIT and graduation rate data released by the Arizona Department of Education. Both the 2016 AzMERIT scores and 2015 4-Year Graduation Rate numbers (the most recent graduation rate data available) show Arizona is failing our kids who do not speak English fluently. On AzMERIT, our English Language Learners are seeing passing rates in single digit percentages (with many grades and subjects reporting pass rates of “<2%”) and only about 25 percent are graduating on time. In this month’s blog, we discuss the performance of students who are non-proficient in English [1], and the historical background of programs designed to support their language development.

Ever Since Flores

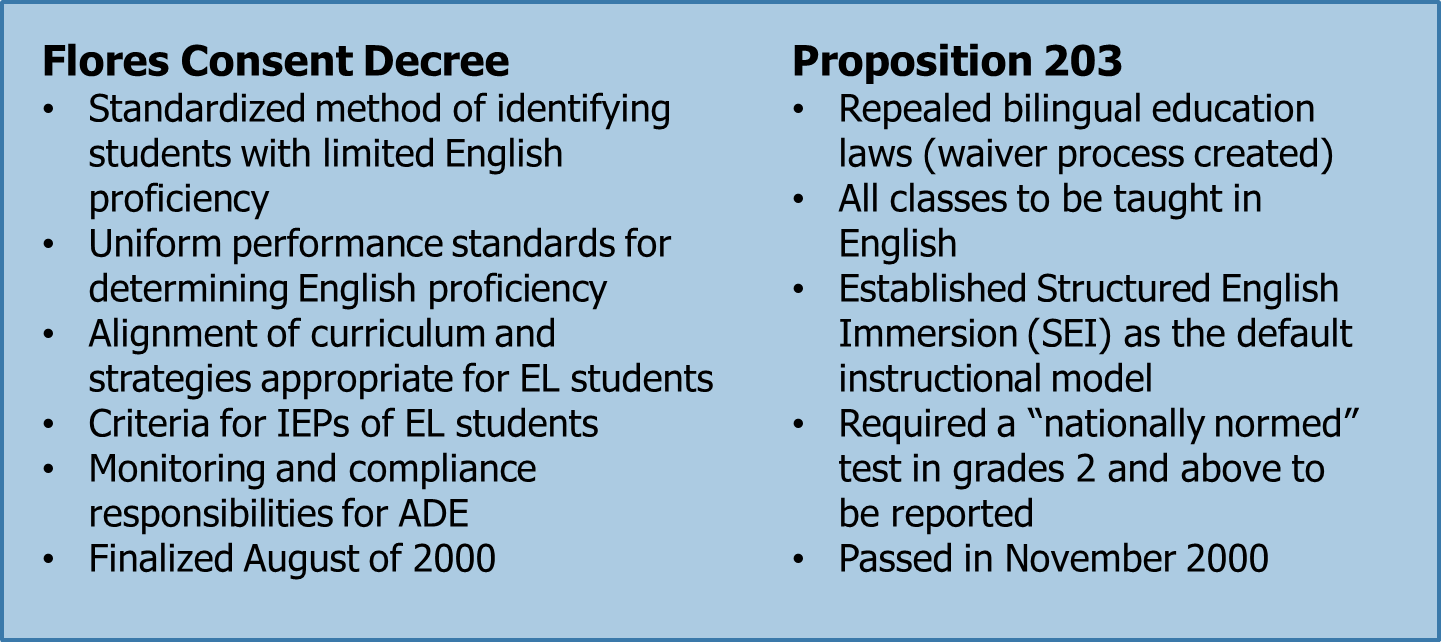

In 1992, parents in Nogales filed suit in federal district court against the State of Arizona. The Flores family contended that their children, who were students in the Nogales Unified School District, had their civil rights violated (along with other English Learner students) since the “state failed to provide a program of instruction that included adequate language acquisition, academic instructional programs and funding for at-risk, low income, minority students.”[2] The District Court ruled in favor of the Flores family in 2000, and the state did not appeal the ruling. State Superintendent Lisa Graham Keegan entered into a cooperative remedy known as the Flores Consent Decree (commonly referred to as “Flores”).

The Arizona State Board of Education and the Department of Education agreed to a number of policy and procedural changes, and left the issue of adequacy of funding to the entity that has the authority to fund schools, the Arizona State Legislature.

Within the space of a few months, Arizona English Language Learner identification and programming transformed dramatically. These changes, compounded by several other significant changes to laws and policies impacting the English Language Learner population in subsequent years, continue to impact the instruction of students in English Language Learner programs.

The timeline below shows the percentage of students classified as English Learners in the years since the Flores Consent Decree was reached. The demographic shift in the size of Arizona’s English Learner student population corresponds to the introduction of the Structured English Language Program language proficiency assessment in 2005 and seems to continue to this day. Significant policy milestones are indicated by the number icons – hover over a point for more information.

Entering and Exiting EL Programs

All Arizona families complete a “Primary Home Language Other Than English (PHLOTE)” form when they enroll in a public school, district or charter. Parents are asked three questions [3] related to the primary or home language spoken with the students. If a parent marks anything other than English, the student must take a language proficiency assessment (formerly SELP, now called AZELLA). Students who do not meet the language proficiency standard set for the assessment are entered into an English Learner program (typically “Structured English Immersion”). These students are often placed in an English language development block for up to four hours a day, based on requirements established by the state legislature. Students are re-assessed at least once each year and if they achieve a proficient score, they are reclassified as a Fluent English Proficient (FEP) student and monitored using state and local assessments to ensure students stay on-track with their peers in terms of achievement.

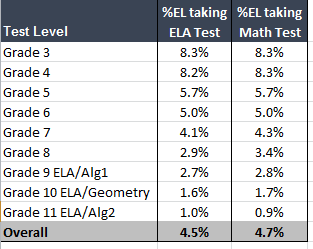

One result of Arizona’s process for determining language proficiency is that the percentage of ELL students is much higher in the lower grade levels than higher grade levels. Though primary grade level information (K-2) is not available through AzMERIT testing, the table below shows the most recent estimations of the size of the ELL student subgroup by grade level, as captured during the 2016 administration of AzMERIT.

Since Flores, it seems that the proportion of students classified as ELL topped out at 19 percent in 2005 and has declined to between 4 to 7 percent in recent years. Now, it’s possible that the number of candidates entering Arizona schools is lower than in the past. However, it’s more likely that fewer students are being identified as ELL and are exiting program status faster. Given the timeline and precipitous drop in the number of identified English Language Learners after the adoption of the SELP/AZELLA assessment, it’s likely the assessments play a large role in this trend.

Concerns have been raised in the past [4] and careful scrutiny of the validation of these assessments is paramount; therefore, a review of the instructional programming tied to assessment results seems prudent. With program entry low, and exit from an ELL program status relatively easy, interpretation of achievement results is complicated. Information on students reclassified as Fluent English Proficient (FEP) is seemingly no longer reported in achievement data sources, and we are left wondering if students recently exited from an ELL program are doing any better. Without public reporting of reclassified student information, evaluation of ELL program effectiveness, and the relief the Flores family sought and won through the courts, is nearly impossible to determine.

Low Pass Rates on AzMERIT, Low Graduation Rates

The Flores family filed their lawsuit more than two decades ago to seek relief and resources to ensure their children, and all ELL students, receive an appropriate educational experience and have the opportunity to achieve challenging state standards. From the recently released state-level AzMERIT results, we see that ELL students are the lowest achieving subgroup reported. In one sense, this result is unremarkable since these students are essentially taking AzMERIT in a language with which students are known to struggle (i.e., English). However, the magnitude of the deficits apparent in the 2016 results is very concerning. On some grade level ELA tests, the number of proficient ELL students statewide could be tallied on one’s fingers and toes. The interactive chart below can be used to examine the 2016 AzMERIT pass rates. The beige bar represents the overall pass rate among a certain group of test takers, while the blue bar represents the pass rate for ELL students within that group of test takers. Hover over a bar to see the information on a given test, or use the filters to the right to narrow the scope of the data.

Along with the 2016 AzMERIT results, the Arizona Department of Education also recently released four-year high school graduation rates for all students and program categories. ELL students have the lowest graduation rate in the state by far, no matter which other category of students they are measured against. Most groups of students, whether they were split by gender, race, or other factors (such as Economically Disadvantaged) demonstrated a graduation rate somewhere between 60-90 percent. For instance, 81 percent of females graduated while 74 percent of males graduated within four years of entering high school. Racial and ethnic groups varied in graduation rates from 66-87 percent. However, students who were categorized as “Limited English Proficient” graduated at a rate of about 25 percent. The interactive chart below shows 2015 high school graduation rates for various groups of students. Details can be accessed if you hover over a circle, and filtering tools (on the right) can be used to narrow the scope of the data.

Viewing English Learner achievement in Arizona in 2016, it appears that the students the Flores Consent Decree intended to protect and better serve continue to struggle. Exclusion of “fluent English proficient” students from published accountability reports may confound the issue, exaggerating the apparent deficit. Without mitigating information, it is hard to conclude that Arizona is living up to the agreement struck 16 years ago to settle this seminal court case.

Footnotes and References

[1] Commonly referred to by acronyms including EL (English Learner), ELL (English Language Learner), LEP (Limited English Proficient), and PHLOTE (Primary Home Language other than English). Local, state and federal data systems still use these terms and more (ESL, FEP, ILLP, etc.) and for Arizona, the debate and discussion around EL students burns as bright and hot as any in recent education policy history.

[2] Arizona State Senate Issue Brief, 12/30/2013. http://www.azleg.gov/briefs/senate//flores%20v%20arizona.pdf

[3] http://www.azed.gov/english-language-learners/compliance/forms/

[4] OCR letter, published here