Along with millions of square feet of vacant and under-utilized school building space, Arizona has thousands of students languishing on wait-lists for high-demand traditional district and public charter schools. Modernization of Arizona's School Facilities Board policy can address both challenges.

Dr. Matthew Ladner, Director, Arizona Center for Student Opportunity

BRINGING ARIZONA’S “GHOST” SCHOOLS BACK TO LIFE

Construction can bring out the worst in human instincts – from the ancient Egyptians, who squandered vast amounts of labor and treasure in creating mountain sized stone tombs to fill with golden objects, to the French monarch, who after an extravagant building binge thousands of years later, prophesied, “Après moi, le deluge.” In more recent history, America’s Savings and Loan crisis led to a large overbuilding of office complexes, many of which were never used for anything other than tax-shelters in the 1980s[i]. Later, a federally funded “bridge to nowhere” in Alaska created controversy and today, entire newly built “ghost cities” stand vacant in China. Such stories rarely end well: grave robbers looted all the pyramids, the Savings in Loan Crisis excesses helped cause a recession, and it is difficult to envision a happy ending for a system irrational enough to construct unoccupied cities. While much smaller in scope, Arizona is experiencing a similar issue in the construction of “ghost school space.” Policy changes could correct it.

The Grand Canyon State is no stranger to ghost towns, many of which arrived at that distinction following the closure of a mine. Just as some of them – namely Crown King and Jerome in northern Arizona, and Bisbee in the south – found renewed life, same outcome is possible for the state’s vacant and underutilized school buildings. In fact, in 2017, the Arizona School Facility Board reported 1.4 million square feet of unused space with information from only 27 out of Arizona’s 235 districts. In 2022, the true extent of vacant or under-utilized school facility space remains unknown.

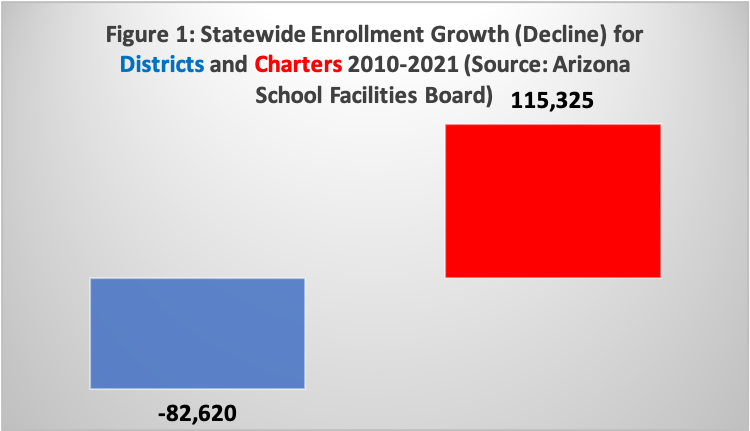

Arizona public districts spent over $8.1 billion dollars on school construction between 2009 and 2019.[ii] As will be demonstrated below, much of this spending is justified by enrollment growth in rapidly growing districts. However, hundreds of millions of dollars have also been spent in districts experiencing enrollment decline – see Figure 1 below – and which already had a great deal of underutilized capacity.

Along with their district counterparts, Arizona’s public charter schools have been growing too and doing the most to accommodate enrollment growth in communities all across the state, but public charter schools do not receive funding from either the Arizona School Facilities Board or from bond and override elections. Arizona’s public charter schools effectively pay for facilities out of operating funds, and receive $1,308 less overall public funding per pupil than districts.[iii] Although they have borne most of the burden of accommodating enrollment growth, they have had no access to the $8.1 billion that districts used on capital, creating new space at the expense of operational spending. As if this were not problematic enough, traditional districts also have millions of square feet of vacant and underutilized school space. Meanwhile, high-demand district and charter schools compile wait-lists of students they cannot serve. Further, despite the broad improvement in Arizona’s academic outcomes, students in many areas still lack access to high-quality school options.

Lawmakers in other states have addressed the issue of providing facilities to high-demand public charter schools through charter school co-location policies. Arizona could be the first state with a co-location policy for high-demand district and charter schools. Such a policy would be building upon the state’s past success in supporting innovative educators to create their own schools. Arizona’s K-12 system is uniquely demand driven.

ARIZONA’S ANTIQUATED SYSTEM OF SCHOOL CAPITAL FINANCE

Arizona’s system of school finance was adopted in 1980, 14 years before the legislature passed charter school and district open enrollment statutes. While those two laws slowly but surely changed Arizona public education for the better, the state’s system of finance has not kept up with the needs of educators or families. Nearly a third of K-8 students in a 2017 study of the Phoenix area attended a district school other than the one to which they were zoned through open enrollment. Another 21% of students statewide attend public charter schools. Arizona students are enrolled in district and charter digital learning programs, home-schooling, and private schools. And, prior to and during the pandemic, micro-schools made their debut. Clearly, family demand plays a guiding role in determining whether school enrollment grows or declines, which schools close, and which schools replicate in Arizona.

Politics however still plays an overwhelming role in determining Arizona facility funding. Specifically, a large majority of school facility funding comes from district bond elections. Many of these elections have been found to be primarily, or even entirely, financed by firms set to profit from construction.[iv] “It’s no secret that it’s the folks that are going to actually be making money potentially off the contracting portion of this that contribute to the campaign,” the treasurer of a campaign group focusing on school bond elections told KJZZ in 2017 [v]. Voter turnout rates in Maricopa County school bond/override elections varied between 7.46% to 41.53% of eligible voters in 2021, with the average turnout across all Maricopa Country bond and override elections amounting to 16.4% of eligible voters.[vi] Various bond elections decided by small percentages of the voting public amid campaigns bankrolled by firms with clear self-interest could in theory aggregate to a coherent facility strategy. No such luck however in our case.

Districts continue to hold on to vacant and under-utilized space, turning what should be education assets into liabilities that pull resources away from classroom use. High-demand district and charter schools continue to have student waitlists, in large part due to a lack of facilities. Arizona districts have millions of square feet of school buildings sit either unused or under-utilized. A 2019 effort by the Arizona legislature to improve transparency with regards to under-utilized buildings, discussed below, has failed to shine a light on the scale of the issue. Improved public policy could turn this around. Taxpayers invested in those facilities in order to fulfill a public purpose: educating students. As discussed below, there are ways for this edifice complex to end productively.

For context, Arizona has two main systems of public education – traditional public-school districts and public charter schools. A bipartisan group of Arizona lawmakers passed charter school legislation in 1994, with the first public charter schools opening in 1995. Also, in 1994, the Arizona legislature passed a statute requiring districts to have an open-enrollment policy, and which forbade the charging of tuition for open enrollment students. Together, these policies created a relatively dynamic system of public education with families playing a key role in which charter schools open, which close, and which district schools gain enrollment through transfers.

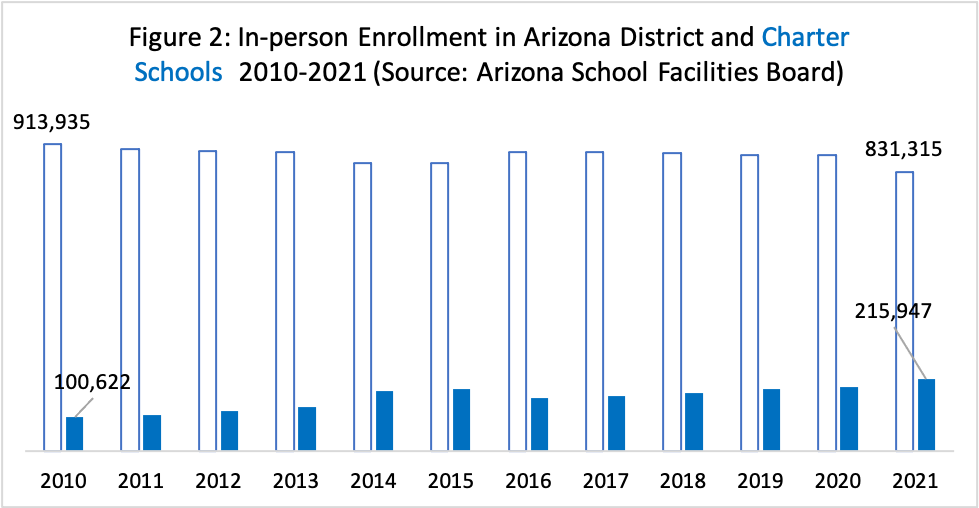

After 15 years of operation, Arizona charters educated over 100,000 students, with the number of charter school students more than doubling between 2010 and 2021, as shown in Figure 2 below. The total statewide increase for in person Arizona public schooling between 2010 and 2021 was 32,705. However, the enrollment increase in charter schools was more than three times greater than this figure, meaning that public charters played the primary role in accommodating enrollment growth during this period.

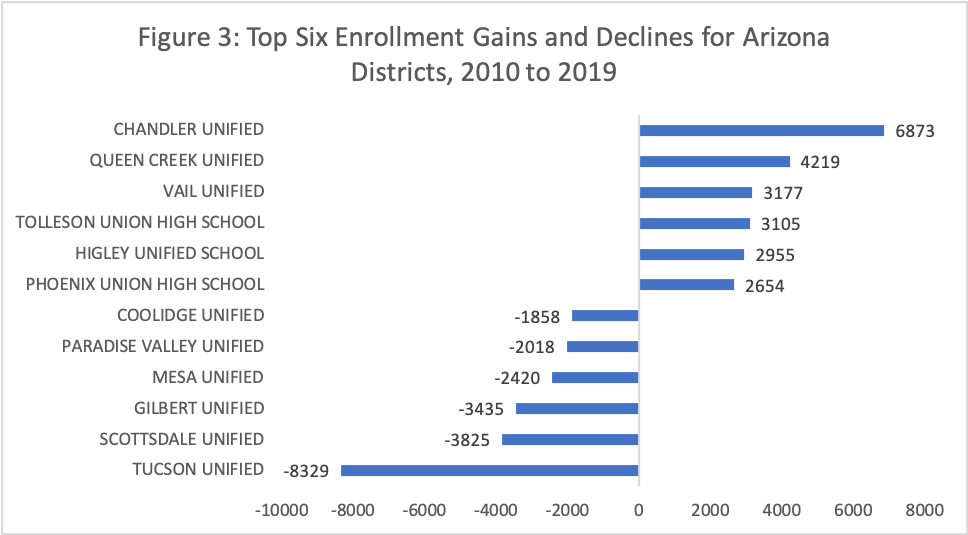

Arizona’s public charter school growth did not however entirely eliminate the need for additional district seats. While Arizona’s statewide district enrollment slowly declined between 2010 and 2021, enrollment varies substantially between individual districts. Some Arizona districts continue to grow substantially, others have experienced declining enrollment. Figure 3 below shows the six Arizona districts in terms of enrollment growth and decline between 2010 and 2019.

Along with family demand for charters, many factors impact district enrollment trends, including but not limited to changing age profiles in communities, fertility rates, migration rates, the demand for open enrollment seats, the demand for private schooling and home-schooling. The United States entered into a baby-bust period largely unanticipated by demographers beginning in 2007, and that trend accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic.[vii] As CNN reported “Arizona, which in the early 2000s had one of the highest fertility rates in the country, saw the largest decline in the number of births of any state over the past decade. It went from nearly 103,000 births in 2007 to about 81,000 last year — a 20% drop.” [viii] Moving in the countervailing direction, Arizona was one of states to gain the most residents during the pandemic with a net increase of 98,330 residents between July of 2020 and July of 2021, ranking third behind only Texas and Florida. As one of the nation’s premier retirement destinations, Arizona’s inflow likely over-samples older new residents relative to other states, but some percentage of those 98,330 residents will nevertheless have been school age children.

FACILITY FINANCING

Arizona districts finance facilities through two main sources: local bonds and state assistance. Between 2009 and 2019 just over $8,000,000,000 in local and state funds was spent on capital outlay between fiscal year 2009 and 2019, in constant 2020 dollars.[ix] A large majority of these funds (over $7.5 billion) came as the result of local bond elections.[x] On the other hand, Arizona public charter schools lack the bonding authority of districts. Charters must either rent or finance their facilities out of operating expenditures. Arizona’s Joint Legislative Budget Committee (JLBC) found that the statewide total public revenue per pupil in Arizona districts stood at $11,153 and the same figure for charters at $9,845 in fiscal year 2020.[xi] The funding to service debt service or rent either ultimately comes at the expense of operating funds, from grants/fundraising or some combination thereof. The COVID-19 era supply-chain problems, and labor shortages has increased the cost of construction, making the efficient use of pre-existing facilities even more critical.

Many of Arizona’s public charter schools have wait-lists of students, the demand for the schools exceeding the ability of operators to supply seats. Charter management organizations have successfully replicated a number of high-demand schools over the years, in addition to new single-site charter schools opening, despite limited funding. A large number of district schools also have waitlists, including in districts with an abundance of underutilized space.

No one should begrudge districts with strong enrollment or growth funds needed to create new facilities, but some Arizona districts have taken on large amounts of facility debt despite being far below the operating capacities of their existing physical plant. In short, Arizona has been spending billions of dollars on school facilities, but not necessarily on those schools that are in high-demand. The state therefore finds itself with millions of square feet of either vacant or underutilized school space and waitlists for high-demand schools. It’s not overly difficult to imagine improving upon this state of affairs.

STRANDED ASSETS AND ARIZONA SCHOOLS

The environmental movement has made a study of “stranded assets” in recent years, assets that have suffered from unanticipated or premature write-downs, devaluations, or conversion to liabilities.[xii] Stranded assets represent a particular interest to environmentalists because, for instance, in the event that people stop burning coal, which would have considerable environmental benefits, there will be assets stranded in the form of coal mines, coal burning power plants, and more. Environmentalists have proposed clever potential uses for stranded assets, for example making use of depleted oil and gas wells for carbon sequestration. If this technique could be brought to scale, it could convert economic liabilities into environmental assets. The question of whether and how to compensate those left with stranded assets due to possible regulatory changes represents an ongoing discussion in the environmental movement.

The issues surrounding vacant district facilities seem simple by comparison. Underutilized school buildings do convert into liabilities due to maintenance expenses and a lack of revenue generated. Under-utilized buildings draw district resources out of classroom use. Districts and the state constructed district facilities exist to fulfill a public purpose: the education of children. In the education field, rather than attempting to develop novel technologies to make use of stranded assets, the process is straightforward: districts can either sell or lease the facilities. While this sounds simple, the politics of the situation complicates matters and a number of states have passed laws mandating districts to make underutilized space available to charter operators.

In Arizona, lawmakers began a process of making such space available to charters, private, or other district operators through Senate Bill 1161 signed into law by Governor Ducey in 2019. The Bill made several changes to state law, including an enhanced process of reporting vacant and partially utilized district buildings by the Arizona Department of Administration and the Arizona School Facilities Board. The law also disallowed districts from discriminating against public charters or private schools when selling or leasing property. The bill further defined a “partially used building” as having at least 4,500 square feet of contiguous unused space, and a “vacant building” as having been unused for at least two years. The legislation also specified that districts could enter into a partnership with a charter school, a school district or a military base in order to operate a school or provide educational services in a district building.[xiii]

While it is early to judge the effectiveness of the 2019 statute conclusively, an examination of the mandated reporting shows a possible flaw in SB1161’s definition of “vacant space.” Below are specific examples, and information on the scale of the under-utilization problem in Arizona. And, we will conclude with potential solutions that are beneficial to Arizona families, students, and the districts with underutilized space.

WAITLISTED STUDENTS, SQUANDERED RESOURCES, AND VACANT DISTRICT BUILDINGS

Between fiscal years 2004 and 2017, Arizona school districts added 22.6 million square feet of building space—a 19 percent increase—despite a student enrollment increase of only 6 percent during this same period. An Auditor General report concluded that districts have “built new schools or added square footage to existing schools in anticipation of increased student enrollment that did not ultimately materialize, and that districts rebuilt existing schools with much larger facilities when no substantial student growth was expected.” The same report found that:

Audits have also identified districts with substantial, long-term excess building capacity that did not take timely or adequate action to reduce the excess capacity. Although decisions to close schools can be difficult and painful, these decisions are important because school district funding is based primarily on the number of students enrolled, and not at all on the amount of square footage maintained.[xiv]

District schools gain and lose students to open enrollment transfers, and to transfers from and to charter schools. Arizona families have however consistently decided against enrolling or continuing to enroll in some traditional district and charter schools. In the case of charters, these schools tend to cease operations. An analysis of a database of closed Arizona charter schools between 2000 and 2013 found that the average closed charter had operated for four years and had an average of 62 students enrolled in the final year of operation.[xv]

As indicated by the Auditor General research noted above, low-demand district schools do not usually face the swift frontier justice meted out by Arizona families to charter schools. Instead, the Auditor General has repeatedly documented underutilized and vacant district space as districts continue to operate under-enrolled schools.

School district governing boards usually face heated community opposition to any school closure. Long before the era of mask and vaccine controversies, the surest way for a school board to summon an angry group of parents to their meetings would be an agenda item pertaining to closure of a district school. Failure to properly manage school facilities however drains resources that could be used to compensate teachers, or for another classroom use. SB 1161 requires the School Facilities Board, in conjunction with the Department of Administration, to annually publish a list of vacant and unused buildings and vacant and unused portions of buildings that are owned by this state or by school districts in this state and that may be suitable for the operation of a charter school.[xvi]

The 2017 version of this report found more than 1.4 million square feet of space in Arizona school district facilities lay vacant or unused. In particular, the 1.4 million square feet of unused space in the Arizona School Facility Board list comes from information on only 27 out of Arizona’s 235 districts. The other 200 districts either self-reported zero vacant space—implausible for many—or failed to report at all.[xvii] For example the Arizona Auditor General’s review of Tucson Unified found that:

In fiscal year 2016, Tucson USD’s plant operations cost per pupil was 31 percent higher than the peer districts’ average because it

maintained a large amount of excess building space. To its credit, the district recognized that it had excess building space and high plant operations costs and closed 14 schools between fiscal years 2012 and 2016. However, the District continued to have some schools with excess space. Specifically, the District’s high schools operated at an average of only 52 percent capacity in fiscal year 2016. Maintaining more building space is costly to the District because the majority of its funding is based on its number of students, not the amount of square footage it maintains. Further, having older buildings and inefficient energy management systems led to the district’s higher energy costs.[xviii]

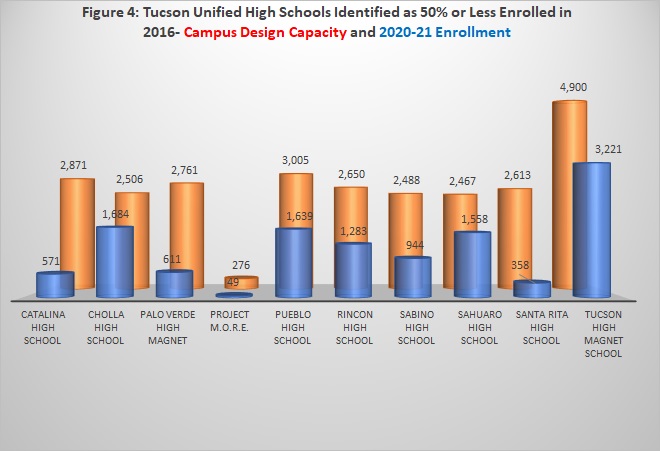

A 2018 performance audit of Tucson Unified by the Arizona Auditor General found in addition to the vacant schools, 10 TUSD high schools operating at an average of 52 percent capacity, with one high school designed for 2,871 students currently serving as few as 761 students, or 27% of its capacity.[xix] That school, Catalina High School, served only 571 students at last count, at less than 20% of design capacity.

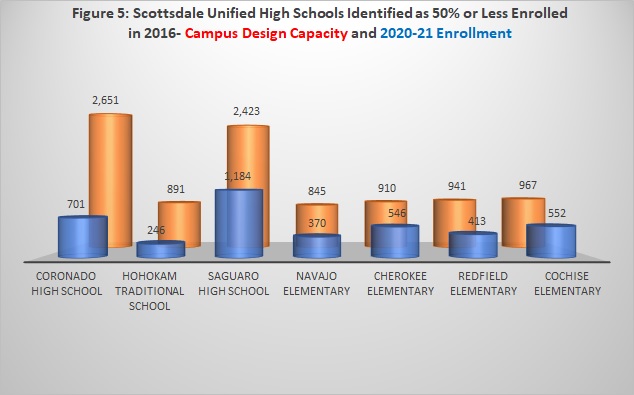

The most recent Arizona School Facilities Board Vacant Space report only listed a group of entirely vacant schools for Tucson Unified District. None of the campuses listed in Figure 4 above listed as having “partially used” space despite each being well below the design capacity of the campus. This may be related to the definition of unused space, discussed further below. In Maricopa county, the Scottsdale Unified School District (SUSD) has been cited by the Arizona Auditor General as having an excess of building space. The Arizona Auditor General recommended that SUSD should continue to review its building capacity usage to evaluate how it can reduce its excess building space as a part of a performance audit in 2015. In a 12-month follow-up, dated June 30, 2016 the Auditor General related that “Although the District has not yet made changes that have substantially impacted its building capacity usage, district officials reported that they are continuing to review building space and utilization. Auditors will review this recommendation again during the 18-month follow-up.” Five and a half years after the 2016 Auditor General follow-up, SUSD continues to maintain multiple substantially underutilized facilities, as shown in Figure 5 below:

The most recent Arizona School Facilities Board Vacant Space report only listed a group of entirely vacant schools for Tucson Unified District. None of the campuses listed in Figure 4 above listed as having “partially used” space despite each being well below the design capacity of the campus. This may be related to the definition of unused space, discussed further below. In Maricopa county, the Scottsdale Unified School District (SUSD) has been cited by the Arizona Auditor General as having an excess of building space. The Arizona Auditor General recommended that SUSD should continue to review its building capacity usage to evaluate how it can reduce its excess building space as a part of a performance audit in 2015. In a 12-month follow-up, dated June 30, 2016 the Auditor General related that “Although the District has not yet made changes that have substantially impacted its building capacity usage, district officials reported that they are continuing to review building space and utilization. Auditors will review this recommendation again during the 18-month follow-up.” Five and a half years after the 2016 Auditor General follow-up, SUSD continues to maintain multiple substantially underutilized facilities, as shown in Figure 5 below:

The Arizona School Facilities Board Vacant Space report currently lists no vacant space for Scottsdale Unified.[xx] The definition of “partially used building” as having at least 4,500 square feet of contiguous unused space seems to leave a great deal of leeway in the definition of “unused.” The data for the Vacant space report is self-reported by districts, and the use of the term “unused” begs the question of what constitutes “use.” It might be possible, for instance, for a district official to deem that a vacant school building with a file cabinet is “used” for storage. The strategic placement of one such filing cabinet per 4,500 square feet, might technically define a “ghost-town” school as not vacant. Such a ploy would obviously violate the spirit of the law, but perhaps not the letter.

What cannot be defined away, however, are the costs of maintaining vacant or underutilized facilities, which will remain regardless of designation on a state report.

Co-Location as a Win-Win Solution for Families and Educators

Under the nation’s most robust co-location statute, the New York City Department of Education must make district space available to public charter schools free of charge. In the event the district fails to provide co-location space, the city is required to provide a charter school with funding on a per pupil basis in order to secure suitable outside space in which to operate. To illustrate, in order to secure alternative facilities, in 2019, New York City provided $80 million to 90 charter schools for which it chose not to provide co-location space.[xxi]

Currently, 31% of New York charter schools operate in co-located facilities.[xxii] In the absence of the co-location statute, few public charter schools could afford to operate in New York City due to the high cost of real estate. Students in district schools, in addition to the charter school students, realize benefits under the policy in the form of higher instructional spending.

In a 2018 study of New York co-location by Education Finance and Policy, a journal published by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, researcher Temple University Professor Sara Cordes examined the impact of charter schools and co-location. Using 14 years of data on over 870,000 students at 584 schools in New York City, Cordes measured the financial and academic impacts on district schools that resulted from charter schools opening either near or on district campuses.

Cordes observes that “co-location may actually be a good policy for both charter and traditional public district schools . . . While charter schools benefit from the relationship financially, [traditional] public school students appear to benefit from improved performance and higher PPE [per pupil expenditures].” Cordes found that traditional public schools experience a significant increase in instructional per pupil expenditure with charter school proximity: co-located traditional public schools experience an 8.9 percent increase in instructional per pupil expenditure, traditional public schools within 0 to ½ mile experience a 4.4 percent increase, and traditional public schools within ½ to 1 mile experience a 2.0 percent increase after the opening of a proximate charter school.[xxiii]

The pattern Cordes observed is not surprising considering New York’s co-location policy requires districts to provide space free of charge in cities with more than a million residents. The National Alliance for Public Charter schools finds that 95.8% of New York charter schools are located in urban areas. The increase in instructional spending found by Dr. Cordes in New York happened despite co-locations usually not generating additional revenue. A co-location policy which required a co-located school to pay a reasonable rent would have the potential to be even more beneficial than the New York policy.

Similar gains in Arizona would translate into a significant funding benefit. Districts spent $11,170 per pupil in Fiscal Year 2020 with 54.9% spent on instruction.[xxiv] An 8.9 percent increase in district per pupil instructional expenditures associated with co-location would thus translate to a statewide average increase of $545 per student. For a class of 20 students, it would equate to over $10,900 of additional funding for teacher pay or other instructional purposes.

Recommendations

For the record, not all Arizona traditional school districts attempted to skirt the vacant spaces reporting statute. For instance, one Arizona district reported its concession stand at their stadium as vacant space. The statute requiring reporting however needs improvement. The Arizona Department of Administration should collect data not on self-reported areas of 4,500 contiguous feet of “unused” space. Instead, data should be collected on the design capacity of campuses and current enrollment. This would increase transparency and could be collected without subjective self-reporting. Policy makers and the public deserve to know basic facts about the utilization of school space, and these data could serve as a foundation for rational policymaking.

State lawmakers should also consider studying reforms to the process of district bonding. While “local control” is a fine principle, the combination of low-turnout rates and campaigns financed by entirely by construction firms represents an unsightly mixture. Lawmakers could consider a standard based upon the utilization of current facilities that would disallow districts with an abundance of underutilized space from bonding. Co-located students however should count for purposes of campus utilization, and districts should retain the option of selling property in order to regain the ability to bond. Moving such elections to the general election date held in even numbered years would certainly increase voter turnout, and thus the degree of democratic legitimacy.

The state should empower the Arizona School Facilities Board to implement a statewide co-location policy based upon state statute. Statute should prioritize both areas with a combination of high academic need, proximate available underutilized space, and district and charter operators with a proven track record. The statute should require the Arizona School Facilities Board to develop a standard contract to serve as a baseline for co-location negotiation and a standardized schedule for negotiations. The contract should specify mutual obligations and rights and responsibilities in a co-location contract, and the hosting district should receive an annual per pupil amount of rent up to the statewide per pupil cost for plant and operations for school districts as determined by the Arizona Auditor general for the previous year.

The Auditor General found that districts spent an average of $1,027 per pupil on plant and operations spending in 2019. Districts holding on to vacant and under-utilized space continue to spend money on the upkeep of buildings. The students of the school co-locating in the campus would help to cover the plant and operations cost on an equitable basis.

The statute should create an annual schedule by which the School Facilities Board identifies underutilized buildings, a request for proposal process for schools interested in co-locating, and establish periods for the negotiation of an agreement based upon the standard contract.

Based upon the experience of other states, Arizona districts may engage in delaying tactics or flatly refuse to enter into a co-location agreement. In such cases, Arizona law should follow the example established in New York and empower and require the Arizona School Facilities Board to certify such districts as out of compliance with the statute, and administer a fine, the proceeds of which will be offered to applicants for the purpose of renting suitable space in the area.

References

i] Downey, Kirstin. 1989. Millions Burned as Real Estate Partnerships Fizzle: Investment: All those people who benefited from depreciation now find those huge write-offs coming back to haunt them in the form of higher taxes. Story appearing in the October 29, 1989 edition of Los Angeles Times, available on the internet at https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1989-10-29-fi-568-story.html.

[ii] Filardo, Mary (2021). 2021 State of Our Schools: America’s PK–12 Public School Facilities 2021. Publication of the 21st Century School Fund, available on the internet at https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5a5ccab5bff20008734885eb/t/618aab5d79d53d3ef439097c/1636477824193/SOOS-IWBI2021-2_21CSF+print_final.pdf

[iii] Arizona Joint Legislative Budgeting Committee. 2021. “Overview of K-12 Per Pupil Funding for School Districts and Charter Schools.” Publication of the Joint Legislative Budget Committee, available on the internet at districtvscharterfunding.pdf.

[iv] KJZZ, and Evan Wyloge, Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting. 2017. “Building Relationships: How AZ K-12 Districts Address Capital Needs.” Report of the KJZZ and the Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting, available on the internet at https://kjzz.org/content/581735/building-relationships-investigation-how-arizona-k-12-school-districts-address#expanded.

[v] Ibid

[vi] Maricopa County. 2021. “Election Summary Report, November 02, 2021.” Report of Maricopa County, available on the internet at https://recorder.maricopa.gov/media/FINALSummary_11022021.pdf.

[vii] Pew Research Center. 2021. “Key facts about U.S. fertility trends before COVID-19.” Report of the Pew Research Center, available at https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/05/07/with-a-potential-baby-bust-on-the-horizon-key-facts-about-fertility-in-the-u-s-before-the-pandemic/

[viii] DePillis, Lydia. 2018. “What does America’s falling birth rate mean to the economy? Just look at Arizona.” Publication of CNN Business, available on the internet at https://money.cnn.com/2018/06/27/news/economy/arizona-birth-rates-economy/index.html

[ix] KTAR, 2021. “Arizona among top states in population growth from 2020 to 2021.” News report from December 28, 2021, available at https://ktar.com/story/4821017/arizona-among-top-states-in-population-growth-from-2020-to-2021/#:~:text=Arizona%E2%80%99s%20percent%20growth%20of%201.4%25%20%E2%80%94%20from%207%2C177%2C986,strong%20growth%20in%20Phoenix%20over%20the%20past%20decade.

[x] Ibid, Filardo.

[xi] Ibid, JLBC.

[xii] Caldecott, Ben, Elizabeth Harnett, Theodor Cojoianu, Irem Kok and A. Pfeiffer. 2016. “Stranded Assets: A Climate Risk Challenge” Publication of the Inter-American Development Bank, available at https://publications.iadb.org/publications/english/document/Stranded-Assets-A-Climate-Risk-Challenge.pdf.

[xiii] Arizona Senate Bill 1161. 2019. Available from Legiscan at https://legiscan.com/AZ/text/SB1161/id/2026043/Arizona-2019-SB1161-Chaptered.html.

[xiv] Arizona Auditor General. 2018. Arizona School District Spending – Fiscal Year 2017, Available at https://www.azauditor.gov/sites/default/files/18-203_Report_with_Pages.pdf

[xv] Center for Media and Democracy. 2015. “CMD Publishes List of Closed Charter Schools (with Interactive Map) | PR Watch” Available at https://www.prwatch.org/news/2015/09/12936/cmd-publishes-full-list-2500-closed-charter-schools.

[xvi] Arizona State Legislature. 2022. Arizona Revised Statutes Section 15-189, available at https://www.azleg.gov/arsDetail/?title=15.

[xvii] Beienburg, Matt and Matthew Ladner. 2019. “Empty Schools Full of Promise.” Publication of the Goldwater Institute and the Arizona Chamber of Commerce Foundation, available on the internet at https://goldwaterinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Empty-Schools-Full-of-Promise-web.pdf

[xviii] Arizona Auditor General. 2018. “Tucson Unified School District Performance Audit: March 2018.” Available at https:// www.azauditor.gov/sites/default/files/18-204_Report.pdf.

[xix] Ibid.

[xx] Arizona School Facilities Board. 2021. “Vacant Space Report.” Publication of the Arizona School Facilities Board, available at https://www.azsfb.gov/sfb/agency/Published/Vacant%20Space%20Rpt%20combined%2004122021.pdf .

[xxi] Zimmerman, Alex. 2019. “New York City charter school rent payments set to climb 54 percent.” Story in the April 4th, 2019 edition of Chalkbeat New York, available at https://ny.chalkbeat.org/2019/4/24/21108001/new-york-city-charter-school-rent-payments-set-to-climb-54-percent-this-year.

[xxii] Jim Griffin, Leona Christy, and Jody Ernst. 2015. “Finding Space: Charter Schools in District-Owned Facilities, 2015.” Publication of the National Charter Resource Center at Safal Partners, available at https://charterschoolcenter.ed.gov/sites/ default/files/Finding%20Space.pdf

[xxiii] Cordes, Sara. 2018. “In Pursuit of the Common Good: The Spillover Effects of Charter Schools on Public School Students in New York City,” Education Policy and Finance 13, no. 4 (Fall 2018): 484-512, https://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1162/ edfp_a_00240.

[xxiv] Arizona Auditor General. 2020. “Arizona School District Spending – Fiscal Year 2020.” Publication of the Arizona Auditor General, available at https://www.azauditor.gov/system/tdf/21-201_State_Page.pdf?file=1&type=node&id=11330&force=.a